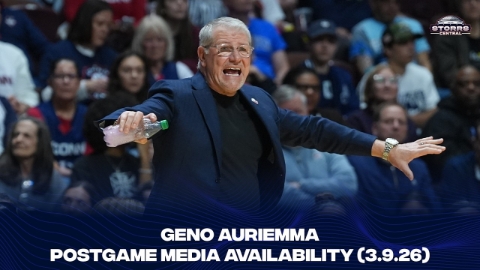

Geno Auriemma has spent the lion’s share of his life in Storrs. He was 31 years old when he became the head coach of the UConn women’s basketball team and just completed his 39th season at the helm. Before Auriemma arrived in Storrs, Huskies women’s basketball posted one winning season in their first 11. During Auriemma’s tenure, the Huskies have won 11 national championships.

Decades before he began his Hall of Fame career in Storrs, Auriemma was a child from a small town in southern Italy whose family made a life for themselves in America.

Geno’s Roots

He was born in the town of Montella in the province of Avellino, a mountainous inland section of Italy made up of more than 100 small communities. But Auriemma was just as shaped by Norristown, the small Montgomery County, Pennsylvania city where he spent the majority of his youth.

The numerous stops he made between Norristown and Storrs further formed the man: Montgomery County Community College in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania; West Chester State College in Chester County, PA; and the numerous day and weekend jobs he held before becoming a full-time coach. His early coaching career included stints assisting the girls' high school basketball program at Bishop McDevitt in Cheltenham Township and the boys' basketball team at his alma mater, Bishop Kenrick, in Norristown. Both Philadelphia-area Catholic high schools have since closed. His path included college assistant jobs at St. Joseph’s University and the University of Virginia, the first position that took him beyond the familiar confines of Southeastern Pennsylvania. The man who shaped Connecticut women’s basketball into the country’s top program reflected the particular set of experiences he encountered along the way.

That way began along the Appian Way, the road the Romans built beginning in the fourth century BC to connect their burgeoning metropole with the southern sections of the Italian peninsula, a region that Rome would soon take by threat and by force. The first such southern region to fall to Rome was Campania, home to Avellino and the community of Montella, which was settled centuries in advance of the Roman conquest. Montella has long been known for its production of chestnuts and the annual festival it holds in the edible nut’s honor. The town of Montella sits in a valley surrounded on three sides by deciduous trees.

Montella’s most famous institution stands in the nearby Folloni Forest, just beyond the town’s formal border. The Convent of St. Francis at Folloni was founded in the 1220s by Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Francis of Assisi, the founder of the Franciscan order and one of the most revered figures in the history of Catholicism. Many sons and daughters of Avellino settled in Norristown, Pennsylvania, leading to the creation of a St. Francis of Assisi Catholic parish and school on Hamilton Street in the city’s West End. The Auriemmas were one such family that ventured from Campania, Italy to Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. St. Francis of Assisi was the Auriemma’s home parish and the place where the Auriemma children went to primary school.

Luigi Auriemma was born on March 23, 1954, in Montella, the eldest of Donato and Marsiella (Biancaniello) Auriemma’s three children. From an early age, the boy was known as “Geno,” a common nickname for boys named Luigi. Both in Italy and America, Geno took frequent care of his younger brother Ferruccio and sister Anna. In Montella, the family had neither a telephone nor a television. Geno rode in his first automobile shortly before coming to the United States.

Donato first came to Norristown in the late 1950s. He resettled the rest of the family in Pennsylvania in 1961. Neither Donato nor “Marsi” could read or write English. Initially, both found work in a candy factory before securing higher-paying, but more physically demanding, manufacturing jobs. Donato made cinder blocks while Marsi sewed carpets at a rug factory. Both walked several miles each day to work. In 1964, the family bought their own home on Norristown’s West End, a row house with a small backyard that served primarily as their garden. Tomatoes and grapes grew in abundance. The Auriemmas had a second kitchen in the basement. That’s where Marsi made her famous sauce and Donato aged his wine.

“I just loved his mom. She was the sweetest thing,” said legendary Virginia women’s basketball coach Debbie Ryan, who got to know the Auriemma family during Geno’s four-year run as her assistant in Charlottesville. Ryan grew up in central New Jersey and shared many points of cultural reference with Auriemma. “[Marsi] was full Italian just like my mom, so we had a lot in common. I understood her. She understood me. My mother’s side was right off the boat,” Ryan said.

“One of the best Italian meals I’ve ever had in my life was in [Auriemma’s] basement,” Jim Foster said. Foster grew up in nearby Cheltenham Township before embarking on a 900-plus win college coaching career that included stops at St. Joseph’s, Vanderbilt, Ohio State, and Chattanooga.

Foster befriended Auriemma at Montgomery County Community College (often referred to as “Montco CC” or simply “Montco”) and gave him his first break in coaching at Bishop McDevitt High School. Like Debbie Ryan, Foster has been enshrined in the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

The life the Auriemmas made for themselves in Norristown was part of a larger boom period in the then-thriving industrial city. Located 20 miles northwest of Philadelphia, Norristown was a quintessential mid-century blue-collar American burg, a manufacturing center that drew migrants from southern and eastern Europe as well as the American South. The migrants from the American South were predominately African American.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Norristown’s West End grew considerably, as builders erected a maze of row house-lined streets that accommodated thousands of young families in search of affordable housing. Aunts, uncles, and other relatives called Donato and Marsi’s place home at different points during Geno’s childhood before finding homes of their own in the area. Each new hour of the morning at the Auriemma household meant that someone else was leaving for work or school.

While the adults worked, Geno looked after his siblings and learned about America. He was the first in the family to learn to read, write, and speak English. He wrote out checks and paid the bills, signed the report cards at St. Francis of Assisi grammar school, and made deliveries for his parents. Geno’s precociousness shone just as brightly in the classroom as it did in the practice of everyday life. By fourth grade, he won a writing award for best composition in his grade. His peers remembered him as a voracious reader who was knowledgeable on a wide range of subjects, a sentiment still widely held by those in his sphere. Even as a child, he was known as a good listener. It helped him learn English rapidly. That skill served him particularly well in his chosen profession.

Surrounding Montgomery County has long been more affluent than Norristown but the disparities between the county’s industrial hub and its environs grew considerably in the late twentieth century. Deindustrialization and divestment from the center city have beleaguered Norristown for decades but an influx of migrants from Latin America kept the city’s population from evaporating in the way of so many other former industrial centers in the urban north. The Norristown of Auriemma’s childhood was roughly 40,000 strong. After dipping to just over 30,000 in the 1990 Census, the 2020 Census counted 35,748 residents.

“Ethnic. Tough. Catholic.” is how Jim Foster described the Norristown of the 1960s and 1970s.

“Norristown was a working-class town, where you represented family with all that you did. It was a tight-knit, family community,” said longtime St. Joseph University men’s basketball coach Phil Martelli, a close friend of Auriemma’s. “It was a very provincial, very parochial, and very prideful area,” he said. Martelli coached boys’ basketball in Norristown for seven seasons at Bishop Kenrick High School (1978-1985). Auriemma served as Martelli’s assistant at Kenrick for two seasons (1979-1981).

The sporting culture of Norristown matched its people. Ball games were rough-and-tumble and ever-present. They were taken seriously and served as visible proof of a young man’s prowess in the world. Confidence was a prerequisite for competition.

Geno acclimated quickly to this environment. He’d loved soccer in Italy but found few such games in Norristown. He caught the baseball bug first on the city’s polyglot playgrounds before embracing basketball. The game he saw on the city’s blacktops exemplified the kind of basketball one found in and around the metropolitan centers of the Northeast. It was a quick, confrontational game notable for the slick ball-handling and bravado displayed by its participants.

Auriemma played both sports through high school at Norristown’s Bishop Kenrick, gradually shifting his fealty from baseball to basketball. By the end of his sophomore year at Kenrick, Auriemma had become a quintessential gym rat, spending every hour he could working on his game.

“It was a basketball area. There were outdoor courts. They were always active,” Martelli said. Norristown High School had long been a regional basketball power, even winning Pennsylvania state championships, a remarkable feat in any sport.

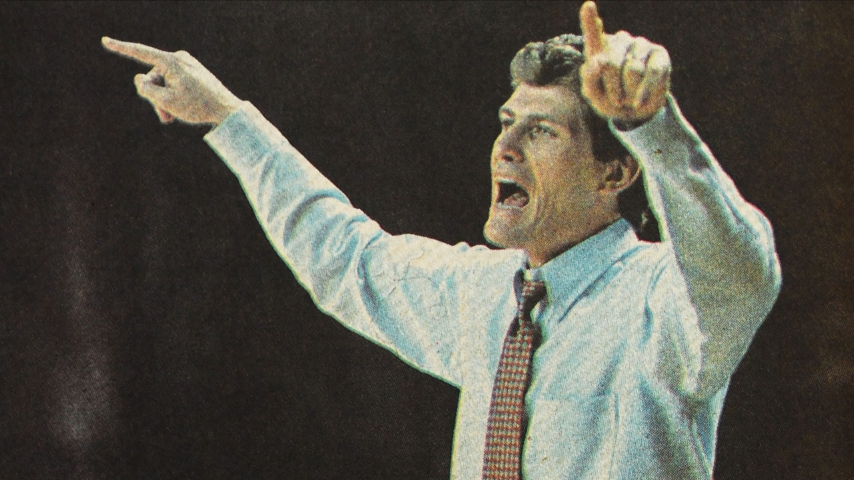

Bishop Kenrick struggled for years to compete with its much larger crosstown rival, not to mention similarly heavyweight peers in the Philadelphia Catholic League, long one of the top high school conferences in the country. Kenrick was one of the smallest schools in the league and struggled for most of the 1960s. They started punching above their weight class in 1969 when a recently graduated St. Joseph’s University point guard named Bud Gardler took over as head coach of the Bishop Kenrick Knights.

By fits and starts, the green and gold became players in the Philadelphia Catholic League’s Northern Division. Kenrick wasn’t at the level of the league’s powers like Roman Catholic High in Center City or Neumann in South Philly but they were no longer an obvious ‘W’ on the schedule. Gardler was acerbic, tough, and focused on the fundamentals. Opponents may have beaten his teams at Kenrick but the Knights weren’t going to be outhustled or outsmarted, or there would be hell to pay.

After six seasons at Kenrick, Gardler moved on to Cardinal O’Hara in Springfield, PA, where he became the winningest coach for a time in the history of the Philadelphia Catholic League.

“Bishop Kenrick was a typical neighborhood school,” Martelli said. “These kids played against each other in baseball, football, and basketball coming up in grade school. Representing and playing for your school team was a really big deal. Even making a freshman team was a badge of honor. There was a lot of pride in the school and a lot of knowledge of the past. People knew the guys that had played there before or coached there before. They were reverent about those that had played before them,” he said.

The Knights excelled in football and baseball. Under a succession of coaches, including Gardler, Mike Lynam, and Phil Martelli, Kenrick ascended to similar heights in basketball. Lynam led the Knights to their lone outright Philadelphia Catholic League championship in 1976.

Auriemma was far from a superstar on Bud Gardler’s team. He was a reserve guard who played significant minutes only as a senior. In Auriemma’s senior season, 1971-1972, the Knights went 4-12 in the Philadelphia Catholic League’s Northern Division, finishing next to last. He averaged 3.5 points per game.

Nevertheless, Auriemma learned the game in a technical sense from his no-nonsense coach. In retrospect, his playing career at Kenrick proved to be a de facto apprenticeship under Gardler, who showed his young charge how to impart the fundamentals of the game. In his earliest assistant jobs, Auriemma displayed striking acumen as a teacher. He was patient and particular but never a nitpicker. Gardler conveyed more than just teaching skills and tactics to Auriemma. He provided his reserve point guard with a sense of how to present one’s self as a coach. Be demanding but attentive. Criticism can be cutting but it needs to be done in pursuit of a tangible goal and not for its own sake.

College Years

Auriemma graduated from Kenrick in June 1972 and pursued higher education at a place where he could continue playing basketball, “Montco” Community College.

In 1993, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia merged Bishop Kenrick with Archbishop Kennedy High School in Conshohocken to form Kennedy–Kenrick Catholic High School on the Norristown campus. In 2010, the Archdiocese opened Pope John Paul II High School in Upper Providence Township, ten miles west of Norristown, leading to the demise of Kennedy-Kenrick, eliminating one of the West End’s longest-tenured institutions.

Decades after Auriemma played at Kenrick, Bud’s daughter, Meghan Gardler, played for Auriemma at UConn after earning Philadelphia Catholic League MVP honors at Cardinal O’Hara. Meghan was a member of the 2009 and 2010 national championship teams, contributing significant minutes at power forward in both seasons.

Getting into Coaching

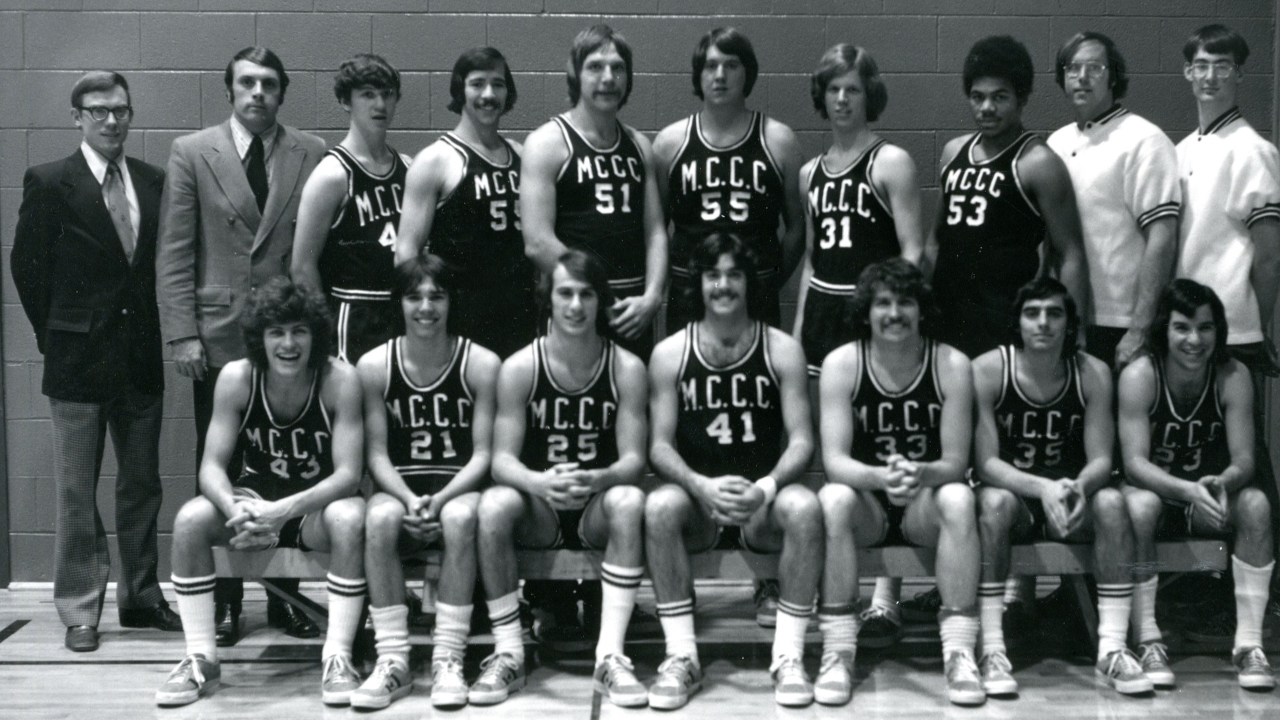

Geno Auriemma enrolled at nearby Montgomery County Community College in the fall of 1972. He spent three years at Montco CC (1972-1975) until transferring to West Chester State College, now West Chester University, where he did not play basketball.

He commuted to the Chester County campus off and on for the next six years before completing his bachelor’s degree in political science in 1981. Geno worked full-time for almost the entire decade between his graduation from high school and the time he left the area to become an assistant coach at the University of Virginia. His occupations included bartender, supermarket clerk, and delivery driver. He sold paint and worked for a time at a steel mill.

Auriemma’s relationship with West Chester State appears to have been primarily in the classroom. He commuted roughly 20 miles to the Chester County campus for class but continued to live and work in Montgomery County. His engagement with Montco CC was much more profound. While working through his general education requirements at Montco, Auriemma played varsity basketball, worked numerous night and weekend jobs, and participated in all manner of intramural athletics. He also met the love of his life and made the connection that got him into the coaching ranks.

“He hasn’t changed much. He was talkative, feisty, happy, and energetic. A good leader and we benefitted greatly from his skills and his character,” Dave Yeo said. Yeo taught physical education at Montco and served as an assistant coach on the men’s basketball team under Gary Hess, a former All-American guard at West Virginia Wesleyan. Like Geno, Yeo arrived on campus in 1972. He coached Auriemma for two seasons.

Auriemma played significantly more minutes at Montco than he had in high school. In his freshman season, he was typically the second guy off the bench. As a sophomore, he started at point guard.

In 1973, Montco won the Eastern Pennsylvania Community College Athletic Conference (EPCCAC) championship and boasted a 21-4 record. Hess preached stout defense and ball movement, later hallmarks of Auriemma’s teams. Montco drew almost exclusively from the county itself. Few Montco players went on to play at four-year schools but Auriemma was surrounded by other talented players, including Wade Stevens, a powerful post player from Norristown High, and Matt Chesterman, an excellent scorer from Abington.

“I didn’t know that this was history in the making here,” Yeo said. “[Auriemma] was coachable and a good learner and a good listener but I didn’t get that hint that he really wanted to go on to coach.”

Yeo credits head coach Gary Hess, a superb point guard who played professionally in the short-lived American Basketball League, for helping to cultivate the attributes that made Auriemma so effective at the position.

“Geno was unselfish. He had the leadership skills as a point guard,” Yeo said. ““He was intelligent and a smart ass then as he is now. He picked up things quickly. He liked people and liked to learn.”

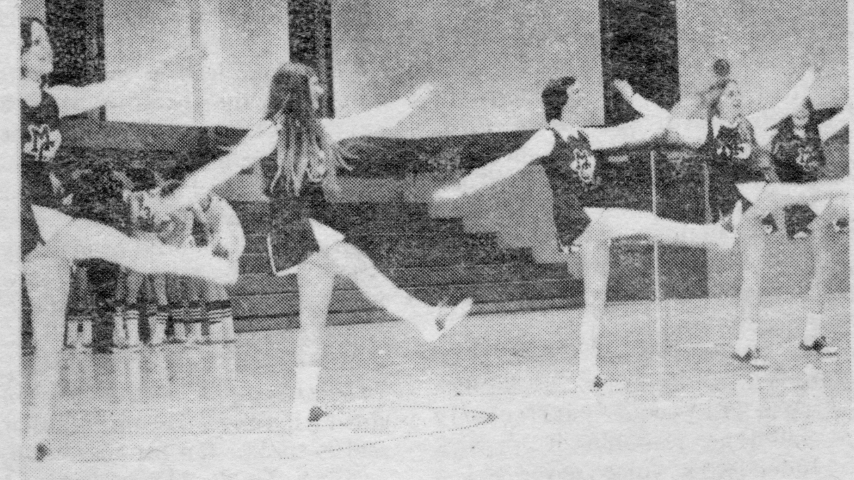

For a two-year commuter school, Montco drew solid crowds to its basketball games. Often, a few hundred students stuck around after class to watch. For Auriemma, the most significant of these attendees was a cheerleader named Kathy Osler.

In December 1972, Auriemma met Osler after a Montco basketball game. Her ride had already left that night and she needed a way to get home. Geno gave Osler a ride back to Elkins Park, an affluent community in Montgomery County known for its collection of beautiful homes designed by some of America’s best-known architects. Kathy didn’t quite fit the mold of the well-to-do town. She lived with her mom in an apartment over a drugstore. Kathy and Geno soon became a couple and have been together ever since.

“That’s a special team, Kathy and Geno,” said Martelli. “Her support and her ability to listen” have made her Auriemma’s closest advisor, Martelli said.

When it came to intramural sports at Montco, Auriemma was a man for all seasons. In the fall, Auriemma was the major offensive threat in the school’s intramural flag football league, quarterbacking a team called the Clams to back-to-back, undefeated championship seasons. The Clams ran over such opposition as the Gallo Brothers, the Seagram’s 7, and a team that went by the name “Denver Broncos.”

Thanks to the intrepid coverage of the Montco student newspaper, we do know that Auriemma led the intramural flag football league in touchdown passes in the fall of 1974. In the spring of 1974, he finished third in the Montco CC punt, pass, and kick competition behind John Brandenberg and Jesse Hodges. Neither could be reached for comment.

In the springtime, Auriemma played varsity tennis, excelling at a sport that shared basketball’s emphasis on agility and manual skill. He competed as both a singles and doubles player for Shelly Chamberlain’s Montco CC team. In spring 1974, Auriemma played doubles with Ty Methfessel for a Montco team that went 8-1 and won the EPCCAC title.

During the winter, Auriemma found time to play floor hockey for a team called the Stanley Cups. Despite their aspirational name, they were apparently the only team Auriemma played for at Montco CC that didn’t win a title.

Besides Kathy, the most significant contact Auriemma made at Montco was a friend he gained while playing intramural basketball during his third year at the school. Jim Foster was several years older than Auriemma and virtually all his fellow students. He’d just left the Army, having served two tours of duty in Vietnam. Foster took on the second tour so that his recently drafted younger brother didn’t have to do one. Despite their age difference, Foster and Auriemma were part of a circle of athletically minded friends.

“Geno was a very good athlete, very quick. Bright. Competitive. And great work ethic. We both had jobs and we both bartended. We were a couple of young kids looking for what was next. Neither of us had any idea it would evolve into what it evolved into,” Foster said.

Foster became an assistant basketball coach at Bishop McDevitt in Cheltenham Township. He spent two years working with the boys before becoming the girls’ head basketball coach in 1975. In his first season, he brought in another friend as his assistant coach. His friend had been a great player but lacked the patience to coach younger players, many of whom had only recently started playing organized basketball. He then turned to Geno, offering him his first shot at coaching.

“I approached Geno and he didn’t jump at it. We had several discussions. We talked about it long and hard and he came along,” Foster said. The pair ended up working together for two seasons at Bishop McDevitt (1976-1978) and then for a season at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia (1978-1979), where Foster began his own storied career as a college head coach.

“There were some very good, very smart players but in general it was going to require a lot of patience and a lot of teaching,” Foster said of his Bishop McDevitt teams. Auriemma served as JV coach while assisting with the varsity. Logistically, the challenges Foster and Auriemma faced at Bishop McDevitt included the slippery linoleum floors on which they had to play, a limited number of baskets, and little court time. They more than persevered. Success came quickly for Bishop McDevitt under Foster and Auriemma. The team reached the semi-finals of the Philadelphia Catholic League in their second season working together.

Watch out for Part II, coming out next week for Storrs Central members only!